In Preparation of the Gonzales Lab

I strongly believe that a PI should actively sculpt a healthy lab culture. If you don’t, who will?

In these last several months leading up to the opening of my own lab, there are dozens of potential tasks to work on. Writing grants, recruiting members, ordering supplies, preparing lectures, getting animal protocols approved, plus online training after training after training after training. On top of this, of course, I have my primary postdoctoral duties as well. There is already so much to do! It is difficult to prioritize when everything feels important. I’m working on all of these things, but by far I’ve spent the majority of my time focused on one aspect: What is life going to look like for the people in my lab?

I thought of this process like a new company with a hip new product. The product (i.e. research) can be amazing, but if the customer (i.e. student and postdoc) experience is miserable, how can I hope to be successful? These people are committing to spend years of their lives under my supervision. I do not take that choice lightly—especially from the first few who are taking a gamble on my own ability to run a lab. I already feel the burden of their trust in me. How do I craft an experience and culture that is sustainable, productive, and fun? How do I realize the vision I have for my own lab, but also give lab members the power to mold it themselves? These are existential questions I will wrestle throughout these next few years. For now, I’ve settled on a few practical steps towards setting the lab culture, being clear about my own expectations, and laying out what students can expect from me.

As always, I drew inspiration from others. To name a few: The Ramirez Lab philosophies, The Chory Lab handbook, The Hoffman Lab resource page, and this Elife article. (Last minute edit: This twitter thread also has some fantastic resources.)

Lab Handbook

My first step was to write a thorough Lab Handbook titled “Gonzales Lab: Mission, Philosophies, and Guidelines.” You can access a PDF version here (although I’m continually updating this document):

I tried to think of everything possible from what is the mission of the lab, to my thoughts on equity and mentorship, to work week expectations, to conference travel. I tried to give both philosophical musings and also practical advice from my own experience. Importantly, I tried to lay out not only my expectations for lab members, but also what they can expect from me. Accountability runs both ways.

Every new lab member is required to read and understand this document. In addition, I make this document available to prospective students as well. It gives a small window into the day to day operations of the lab.

I’m fully aware of my own naivety and lack of experience. I say there is about a 70% chance I look back on this document in five years and realize I missed the mark in several places and maybe completely failed in others. That’s ok. I’m absolutely prepared to take both the wins and losses with this job. That’s why I think of this as a living document. It isn’t stagnant or frozen, but on ongoing project. I will update it as I gain experience and narrow in on my own policies. I’ll also take into account feedback from the lab, which they have the opportunity to regularly provide.

Lab Onboarding

After finishing this document, I kicked up my feet and poured a glass of whiskey. Ahh. It feels good to be a thoughtful PI. That feeling lasted for a few minutes. Until my mind spiraled into the realities of having new students under my supervision. That’s like…a big responsibility.

Do you remember navigating that first year of your PhD? I was so unprepared. There’s a strange conundrum of both too many things to do and learn, but also not being able to actually do any of them yourself without a more senior member holding your hand. You know a funny story about me? As an incoming graduate student, I had no idea what a pipette was. I came from a physics background. I was used to high vacuums and radiation and lasers, but had never moved tiny amounts of liquid from one vial to another. My second day as a PhD student, an undergraduate was training me on a simple process.

“Ok…first you need a pipette,” she said.

“Cool, cool,” I said. “…what’s that?”

I can still see her face. Horror mixed with thoughts of how did this guy get into a PhD program?

Anyway, I don’t care whether the students I recruit know what a pipette is. It takes 60 seconds to train them how to use one. What I do care about is facilitating their integration into the lab. In fact, what are even my own expectations for new lab members? “Getting up and running in the lab” is such a vague, inefficient process that thousands of graduate students undergo every year. What does that actually look like week to week? How can I make that process more efficient so that students don’t feel like they’re aimlessly flailing for months on end?

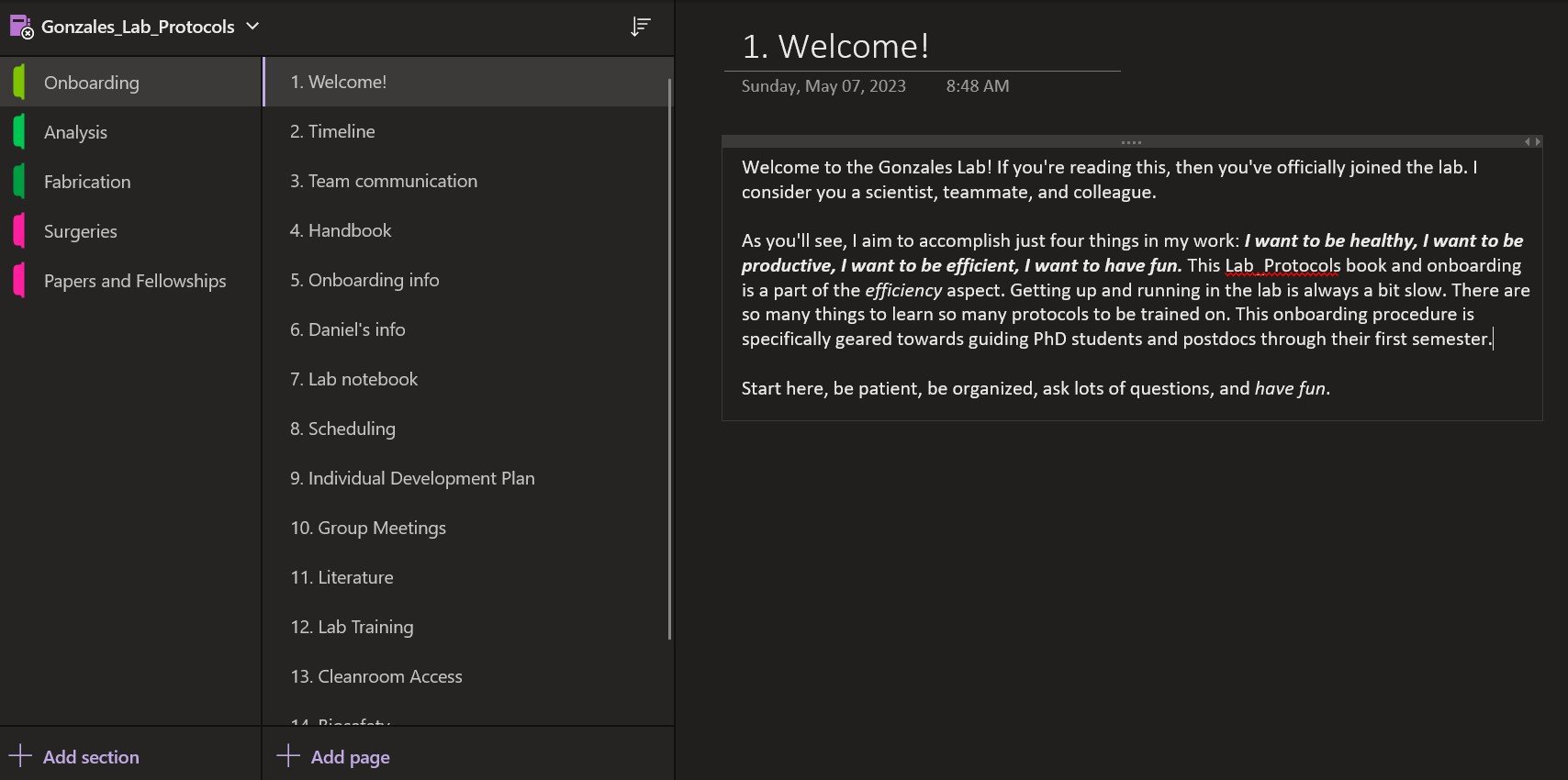

I narrowed in on this question by focusing on what a new PhD student should accomplish in the first semester. They have a huge task! They have classes, safety training, TA’ing, learning lab protocols, learning about their projects, and so much more. I decided to draw out a timeline of major goals that extends through their first semester. This “Onboarding” workflow is found within the lab’s internally shared “Lab Protocols” notebook. This holds all of our step-by-step experimental protocols and other important information. Here is a snapshot of the onboarding procedure:

This onboarding procedure walks them through every step they need to get acquainted with and integrated into the lab.

Welcome - Brief welcome message and purpose of onboarding

Timeline - An approximate timeline of how long these tasks should take

Team Communication - How the lab stays in contact with each other

Handbook - They read the Lab Handbook (if they haven’t already during the recruiting process)

Onboarding Info - They complete and Google Form with info like name, contact info, dietary info, and info that goes on the lab website

Daniel’s Info - Just simple info like my office lcoation, phone number, etc

Lab Notebook - How to start an (electronic) lab notebook, where to store it, and how to structure it

Scheduling - How to use shared lab calendars for lab events and booking specific lab equipment. Also provides access to my personal calendar and how to schedule one-on-one meetings with me

Individual Development Plan - They complete an IDP (see more info below) which tells me more about their goals, stresses, and what they expect from me as a PI. After completion they schedule a meeting with me

Group Meetings - A quick primer on when meetings occur and their purpose. They also have to schedule a time to present their first presentation to the lab, which is a brief intro about themselves, their background, and general idea of their own project

Literature - They download Zotero and join a GonzalesLab library. This has curated papers and notes on why the papers are important. (it also forces everyone to use the same citation manager). I also provide general advice on finding and reading papers, and expectations for the approximate numbers of papers they should be reading.

Lab Training - This is an attempt to semi-standardize how lab training happens. For example, they will never be shown a procedure that does not have a written protocol. During training, they will follow the protocol step by step. Depending on their project, students prioritize either microfabrication training or animal surgical training

Cleanroom Access - Details the institutional training and requirements for gaining access to the cleanroom for microfabrication. I also outline a priority list for the cleanroom tools to be trained on and fabrication processes to know before the end of the semester

Biosafety - List of institutional biosafety trainings required for working in our lab and the cleanroom

Animal Certifications - trainings and procedures required for working with animals (i.e. reading the IUACUC protocol, vivarium orientation, animal handling trainings, etc.)

Throughout the process, I focus on becoming independent as quickly as possible. I believe lab independence is the most critical factor to getting a project up and running, exploring potential directions, and “feeling” like a PhD-level scientist.

Individual Development Plans

Within the onboarding workflow, you’ll see a step called “Individual Development Plans” (IDPs). I know what most of you are thinking….YUCK. It’s extra work for the PI and the lab. It can feel overly awkward and bureaucratic. BUT…I’m giving it a try anyway. Remember: the PI sets the culture. I think we can do these in a way that is fun, encourages a growth mindset, and gives me avenues towards being a better mentor.

I modeled my lab’s IDP off of templates from both the NIH and my own institution. However, I molded it to fit the unique culture of my lab (i.e. added some goofiness to it) and added in some aspects I’m particularly interested in tracking throughout the PhD experience. I’m interested in how their goals shift and change over time, but also how I can help facilitate those goals. I want to open a door to conversations about stress and mental health, and also want to discuss ways to manage stress levels and balance work/life. Also what do they specifically expect and need from me as a PI and mentor? I would much rather them tell me then having to guess on my own.

Like every other document, these questions will likely change and morph over time. Overall, I genuinely hope that in five years I can look back over these answers with students and see a track record of resiliency and growth as both a scientist and human. I also hope I take the feedback in stride to become a better PI. Together we can set the lab culture.

Conclusions

Am I thinking too much about all of this? Probably. In true physicist fashion am I over-engineering this whole thing? Maybe. In the best case scenario, I’m laying a foundation that will hold up an entire laboratory of people for decades to come. In the worst case, I’ve done the equivalent of writing a rejected grant proposal for a new project. But you know what? Those ideas are down on paper now. I’ve pulled the vague fog of thoughts out of my head and formed them into a semi-cohesive plan of action. It’s a plan that can be built upon, added to, torn down in some places, and reconstructed in other. Let’s roll.