For Prospective PhD Students

Updated 10/09/2023 to include info on application fees/waivers, stipends and compensation.

Updated 09/22/2024 with new info and preferences on reaching out to PI’s in advance of applying.

What are labs looking for in prospective PhD students? How should you initiate conversations with the PI? What type of research experience are programs looking for? These are some of the main questions on the minds of aspiring PhD students. If you’re applying for programs this cycle, hopefully you’re thinking hard about these topics. This blog is an attempt to give some answers based on my overall approach to recruiting. It’s a window to some of the hidden curriculum behind the process (at least from my point of view). I take a significant amount of inspiration from this perspective piece by Científico Latino, which proposes that one small way that PI’s can increase equity and access to PhD-level education is to be more transparent about their expectations for PhD applicants. Another great resource is this piece by Dr. Talia Lerner at Northwestern University.

In all honesty, I hesitate to write this. What do I know at this point? My lab hasn’t even officially opened and I have so little experience in hiring and recruiting. Yet, for some reason, I sort of just know what I’m looking for. Here are two random things I take comfort in when it comes to sharing my (potentially naïve) opinion on this topic:

Established professors run their mouths all the time with all kinds of bad opinions on twitter (ugh…X). Their public shouting weirdly empowers me to share in this blog what I think are some pretty good thoughts.

This exchange between the infamous music producer Rick Rubin and CNN broadcaster Anderson Cooper (see the video here):

Cooper: Do you play instruments?

Rubin: Barely.

Cooper: Do you know how to work a soundboard?

Rubin: No….I have no technical ability…and I know nothing about music.

Cooper: Well, you must know something.

Rubin: Well, I know what I like and what I don’t like…and I’m decisive about what I like and what I don’t like.

For some reason, I’m decisive about what I like and what I don’t like.

As a disclaimer, many of these answers are very specific to my philosophy, my lab, and my opinions. Some points generalize broadly to other programs and PI’s, but not all of it. Every PI and PhD program is different. In fact, I’ve seen other professors take drastically different viewpoints than my own. I’ll try to point those out as we go along. Also, this perspective also doesn’t necessarily reflect the views of my own department. For the official admission requirements into Vanderbilt Biomedical Engineering (VU BME), see this link.

Here is an overview of the topics I cover:

Know the application requirements

PhD stipends and compensation

Application fees and waivers

Should you reach out in advance of applying?

How to reach out

When to reach out

What to say when you reach out

Does GPA matter?

Should you have research experience?

Should you have relevant research experience?

What type of research experience should you have?

What results should have come out of your undergrad research?

Non-academic jobs and experience - should you include it?

What happens during our first zoom meeting

What happens during follow up meetings

Qualities I look for during our meetings

When do formal interviews happen?

Additional resources

Along the way, we’ll review some encouraging tweets:

@NikhilBasavappa tweet: “I am becoming increasingly convinced that the best part of a PhD is the summer before you start it, when you get to tell everyone you’re doing a PhD and they’re all like “oh so cool” but you don’t have to actually do any of the PhD yet.”

First things first: know the program requirements.

Before doing anything, review the eligibility and application requirements for the PhD program you’re interested in. Don’t email professors or grad program directors with questions that are easily answerable. If you start off our very first interaction with an email asking “Is the GRE required to apply?” it’s immediately not a good look. This answer is easy to find. (VU BME does not require the GRE, btw). Some helpful links for VU BME: Application Deadlines, BME FAQ, BME Admission Requirements.

PhD stipends and other compensation

This is a RED ALERT for some of you!! Most PhD programs in science and engineering will come with free tuition, a stipend, and health insurance. I didn’t know this until the summer before my senior year as an undergraduate. I was completely shocked. Graduate school was always on my radar, but I didn’t give it much thought because of cost. I couldn’t even afford my undergraduate degree without my scholarships, and didn’t want to go into debt just to go to more school. Realizing that PhD programs not only came with tuition waivers, but also stipends and health insurance options, completely rocked my world. Pursuing a PhD was a no brainer for me from that moment on.

There are some caveats here and more details to be aware of:

Tuition is covered, but fees typically aren’t. This can still be a significant amount of money each semester. You can find more info for VU engineering fees and tuition costs here.

Next, there’s the stipend. I have such complex feelings about PhD stipends that I could fill up an entirely different blog. But essentially, you get paid to go to graduate school. How much you get paid can vary drastically between institutions. The VU BME stipend is currently $35,000/yr. Some institutions pay more, many places pay less. My starting stipend as a PhD student at Rice University was ~$28,000. You can also apply for prestigious graduate fellowships like the NSF GRFP and NDSEG, which pay $37,000 and $43,200, respectively. My complex feelings stem from the fact that these numbers can be tough to live on, particularly with the recent years of inflation and soaring housing costs. However, some of you are in the same boat I was went entering grad school. You don’t see these numbers and think “omg this is exploitation.” Instead, you see these numbers and think “omg this is more money than most of my family makes! I’m going to be set!” I was so pleased with my $28K/yr. Thrilled actually. Yet, we should all still advocate for better wages for PhD students. Anyway, take stipends and cost of living into account when searching for programs.

Final note on stipends: Again, program stipends will vary widely. Some may offer a stipend, but not guarantee it past 1-2 yrs. I received one of these offers, and it was from a place I had always dreamed of attending. (I’m not pointing fingers, but it was the UT Austin Nuclear Engineering program.) I walked away immediately. It just wasn’t worth it to me. You need to assess these offers based on your own situation and make an informed decision.

Lastly - health insurance. Most programs will offer graduate student health insurance. But, as with stipends, the monthly premiums and quality of insurance can vary widely. My graduate insurance was still really expensive and a constant stress. Inform yourself about these things.

Application fees and waivers

Applying to multiple graduate schools can be expensive. Anywhere from $50-150 per application. Just be aware that waivers are available! Nearly every school should have a method to request an application waiver. Use these extensively and don’t feel bad about it. I’m not sure anyone knows where the application fees even go.

Should I reach out to professors before the application deadline?

For my lab, feel free to do this (I’m not sure about the preferences of other professors). I would generally say this is a good idea overall, especially for departments that are direct-admit like VU BME. Direct-admit means you are admitted directly into a lab. Other departments may instead admit you into the program, followed by a rotation period during your first 1-2 semesters to find a lab.

I have a very specific reason for why I prefer to interact with prospective students before and after applying: I take hiring very seriously! I admit - I’m quite picky about who I recruit into the lab. PhD students shape the lab culture. These first few students will lay the foundation of the Gonzales Lab for years to come. Therefore, I don’t just rely on your application and one formal interview. We will meet several times (I elaborate on this more below).

Update 09/2024: I now found myself overwhelmed with the amount of inquiries I get. It’s hard to keep up with, sometimes difficult to respond, and impossible to meet with everyone. I used to try and meet with everyone, but have since updated this policy. Now I generally plan to begin meeting with candidates who receive an invite to interview. These invites are sent out in early January after we review applications, and the visit happens in March. This gives us a ~3 month window to meet a couple times, then once again during the in-person visit.

How do I reach out?

Send me an email. I’m also always open to a well written DM on twitter (X...ugh). (This is an example of something I’m cool with, but a lot of professors are not).

When do I reach out?

There are two different good times to reach out to me. One, you can reach out well in advance of the application deadline, anywhere from 1-6 months before. Honestly it could be a year in advance. I like people who think ahead. Note that late Fall near the application deadline can get really busy. So, one strategy may be to reach out over the summer.

After applying to the program and the department reviews applications, you may be invited for a formal visit to VU BME. These invites get sent out in December and January, and the visit usually happens in March. The ~3 month timeframe between the invite and visit is another great time to email. I may also email you! I try to get a head start on recruiting well in advance of the in-person visit.

What should the email say?

This is the tough part. You don’t want to be too brief, but you also don’t want to be too long. The most important rule is don’t be generic. If it looks like you sent this exact email to dozens of people, I’m much less enthusiastic to respond. Feel free to use a tool like ChatGPT, but also be sure to tailor and edit its output to your voice and your true curiosities. ChatGPT can also be overly formal. While I love being called an eminent scientist and renowned researcher, let’s be real. Most people know me for my bbq pics and silly tweets.

You should introduce yourself, your institution, your major, and quickly discuss the research area you are interested in pursuing. Also - it’s totally ok to not be sure what research area you want to pursue! I completely believe in exploring a lot of topics and labs to find one that excites you the most. Then, you can mention why my department and my lab is a good fit for your interests. It should be obvious that you are aware of some of our primary areas of expertise. Feel free to mention that you are planning to apply to the program (or have already applied and received an invitation to visit) and would like to meet to learn more about the opportunities in my lab. I try to meet with most people who reach out, but as the number of requests I receive continues to ramp up I may not be able to sustain that. Finally, attach a CV with more details like your GPA, research background, and other activities you are involved in.

Check out the cover letters I sent when applying for postdoc positions here. They are a pretty reasonable guide for how to structure an email about a PhD program and lab too.

@CollegeStudent tweet. “Emailing professors be like Me: polite greetings, multiple paragraphs, perfect grammar Professor: “sure” -sent from my iPhone.”

Does GPA matter?

Of course, GPA matters. However, individual PI’s weigh GPA differently. For me, I basically try to weigh all GPAs 3.5 and above equally. If you’re above this threshold, I quickly move on to recommendation letters and personal statements. For GPAs lower than this, I’ll take a close look at the transcript. Ideally, you have a higher GPA when considering only the core curriculum for your major (e.g., engineering or physics courses). It’s also encouraging to see if your grades ended strong after starting out on the low end in the first year or two. I’ll also strongly take into account if you are balancing big workloads. If you work part- or full-time to make a living while going to school, that goes a long way for me. If you have dependents or family to care for, that also goes a long way for me. However, it is your job to bring this to my attention! In your personal statement and CV, you have to somehow show that despite all of these obstacles, you still did pretty well in your courses. You can also have your letter writers point these things out.

Another note here is that many PI’s strongly prefer GPAs well above 3.5. I get it. A high GPA shows that when you give a topic your full attention, you can master it. This is an important skill during a PhD. However, in the same way that “book smart” and “street smart” are very different, I think there is a big gap between being “course smart” and “lab smart.” I’m looking for people who are going to be successful researchers, not people who can get a A in every course.

(FWIW, I had a 4.0. GPA. I haven’t gotten to brag about it in a while. So let me take this opportunity. It’s my blog. I get to do what I want.)

Should I have research experience?

Our official department stance is “strongly recommended,” and I echo this stance. I understand that research experience often means uncompensated time that many marginalized communities simply do not have. However, it’s a reality that the vast majority of applicants have some type of research experience. Research experience was strongly preferred more than a decade ago when I was applying, and the bar is significantly higher now.

From a very practical standpoint, also consider that research experience can be very eye-opening to a lot of people who thought they would really love it. Lab work can be lonely, tedious, and slow. It’s not for everyone and it would really suck for you to come to that realization after moving across the country to join a program. As an anecdote: the cohort of physics students I graduated with back in the day had maybe 10 students with the credentials to get into a quality PhD program, but only two or three of us even applied. The rest? An REU program or other undergraduate research experience showed them they didn’t actually enjoy working in a lab very much.

Should I have relevant research experience?

Of course, every PI prefers a research background with relevance to their own work. It blows my mind to see students with experience in device design, microfabrication, or any neuroscience work. However, I really do consider all candidates with all types of research background. What I care most about is that you dedicated yourself to time in a lab and sought out research experiences to expand your skillset. My job is to train you to do the work you want to do, not just recruit people who are already PhD-level scientists in my field.

Again - remember that this is my personal approach. There are definitely PI’s that simply do not consider candidates without direct experience in their field. This is wild to me, and I could rant in an entire second blog about it, but just accept that sometimes this is how it goes.

What type of research experience should I have?

There are two primary ways most undergraduates get research experience. One, a summer Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU). Two, working with a PI at your home institution for a few semesters. Neither is required for admission, but both are valuable for different reasons.

An REU shows that you actively applied and sought out external research experiences. It probably ended up being more boring than what you anticipated; regardless, these experiences give you a perspective on academic research you probably wouldn’t have gotten otherwise. In the best-case scenario, it exposed you to a field of research that you became passionate about pursuing for a PhD.

I also value consistent lab work at your home institution. It really stands out to me when someone has stuck with a lab for 2-4 semesters. Is this a requirement for my lab? Absolutely not. But I think most people would agree that the majority of undergraduates that join a lab typically observe a few experiments, tinker around a bit, then disappear in 1-2 semesters. So, it stands out to me when you stuck with one lab and juggled that extra workload with your classes. If you’ve bounced around between a few labs, that’s also ok. The most important thing is having one of your research advisors vouch for you in their letter, which brings us to the next point.

Undergraduate research deliverables: letters of recommendation, papers, presentations

I mentioned this above, but to me the primary deliverable of your undergraduate research experience should be a strong letter of recommendation from a research advisor. This person should be able to point to your work ethic, ability to solve problems, and specific things you worked on. Again, if you’ve spent multiple semesters in this lab, this letter writer will have a lot to talk about.

In addition to the letter, you should be able to communicate intelligently about your undergraduate work. This is very vague, I know. But basically in an interview it can be easy to tell if someone tinkered around a tiny bit and added those things to their CV versus someone who really dove into a project.

Research can also lead to presentations. Most institutions have annual undergraduate research symposia, and it’s a great idea to participate. A nice thing about REUs is they almost always end in a summer research symposium. Also, if you made a substantial amount of progress on a project, your advisor may have allowed you to attend and present at an external conference.

Lastly - the dreaded Undergraduate Publication. Are you a co-author on a publication? Fantastic. It means you made a considerable contribution to a project which can only be done through a significant amount of dedication. Are you first author on a publication? Wow! Truly impressive and a rare feat for an undergraduate researcher. Do you not have any publications? Don’t sweat it. I’m looking for people with a history of a strong work ethic, an innate curiosity, and an ability to think and dream big.

Non-academic jobs and experience - should I include it?

I am a huge supporter of two things not related to research and education: having a job while an undergraduate or showing a substantial dedication to an organization.

I’m going to go full force here: I think having a 20+ hr/week job and balancing a full course load (plus even some research) is the best preparation for graduate school. Grad school is quite literally balancing full-time coursework with an entire second job of working in a lab. Some undergraduates have the luxury of dedicating their entire time and energy to doing well in their courses while being financially supported by family. You’re lucky and I fully expect your transcript and CV to reflect this advantage. For those of you who balanced jobs throughout your undergraduate education: I am such a fan. Please please please include these jobs on your CV and weave them into your personal statement.

In addition to a job, I really appreciate people who show significant dedication to something/anything outside of classes and lab. This can be a campus organization, athletics, local church, 4H, DEI initiative, or activism. I really don’t care what it is, but I think that displaying dedication and passion for something that took up a substantial part of your time just indicates a solid personal quality.

First zoom meeting

Ok so you emailed me (maybe after sending me a reminder email probably), and we setup a meeting to chat. I try to keep this informal! I know you’re probably nervous, but just know that on my end I’m always excited. I’ve met so many incredible students who will go on to do great things. These conversations can be one of the best parts of the job.

Generally, I’ll try to keep this first meeting focused on you, your interests, your long-term goals, and whether my lab fits those interests and goals. Somewhat counterintuitively, I’ll actually avoid going into depth about science. Of course, we will talk about my research program and open projects in my lab, but I really try and keep this first conversation focused on getting to know you (and letting you get to know me). I want to know how you got to be where you are today, how you made the decision to pursue a PhD, and where you see yourself going in the future.

I’m taking this approach for a few reasons. For one, science is about people. I want to demonstrate even in our very first chat that I care about more than just the science. Two, communication is key to our long-term success together. If things ever go bad, communication will be the first thing to break down between us. So, I want to see our communication start off strong—even in the absence of an in-depth conversation about science.

Follow-up meetings

If our first meeting goes well, I will almost certainly schedule follow-up meetings. It’s in these meetings that we can dig into some project ideas and brainstorm together. I’ll also likely send some papers for you to look over and I’ll ask for your thoughts on them.

What I have my eye out for in our meetings

Here are some things that really stand out to me during these meetings:

Questions. Ask a TON of questions. Ask fun questions. Ask hard questions. Try to trip me up with questions. Ask science questions. Ask questions about papers. Ask questions about my projects. Ask questions about mentorship. I love it. It shows you are curious, inquisitive, and want to make a very informed decision. It shows you’re thinking and it’s hard to train someone to think. See the end of this blog for links to some solid interview questions.

Show me you’re interested. I may think you’re a great candidate, but I also need to know you are genuinely interested in my lab and Vanderbilt! Be responsive to emails. Show up prepared for our chats. Have lots of questions. Read the papers I send you. Read up on my field. Read up on my lab - I have a ton of documents on this website that give you insight into how the lab operates. It goes a long way for me to know you took the initiative and read these in advance (like you’re doing right now - great job!).

Dream big and be creative. When we’re talking about science, I hope you have wild ideas. Some might be great ideas, others bad. Some may have been done already and others might be infeasible. Toss them into the conversation anyway. Show me you’re thinking. Even if neuroscience and neuroengineering are completely new realms for you, I think a lot of great ideas spring from naïvety. I think the best scientists around take their cumulative experiences, interests, and backgrounds and shape them into completely unique research directions.

Be up for anything. I like someone who is broadly curious and willing to take on any challenge. Don’t be too rigid in the type of project you’re looking for. Too often people narrow themselves into a corner way too early in their careers. Don’t show up with the attitude of “I have experience in X, so I’d like to continue working on X.” It’s a PhD. The whole point is to learn a ton of new things.

Don’t worry about being wrong. If I ask a question, it’s ok to not have the answer. A solid quality of a good scientist is knowing that you don’t know all the things. Case in point:

@saahireshafi tweet: “Before a PhD: I don’t know. After a PhD: That is outside the scope of my current knowledge.”

What about formal interviews?

As I mentioned earlier, after your application is reviewed for VU BME, a subset of applicants are invited for an in-person recruitment event at VU. This is where the bulk of recruiting typically happens. You get to meet faculty, hang out with graduate students, eat good food, and have a ton of fun. You will also have formal interviews with the faculty you’re interested in working with.

I personally find it really difficult to make a hiring decision based only off of the interview time. This is why it’s a good idea to reach out in advance of the application deadline or recruitment weekend. We can meet virtually in advance and get to know each other! If the formal interview is our first meeting, I’ll schedule follow up virtual meetings with applicants I want to know more about.

Final resources

Científico Latino has excellent resources for everyone on step-by-step guides for applying to graduate school. They offer guides, webinars, and also an entire mentorship program for underrepresented students. I highly recommend checking out their website and getting involved.

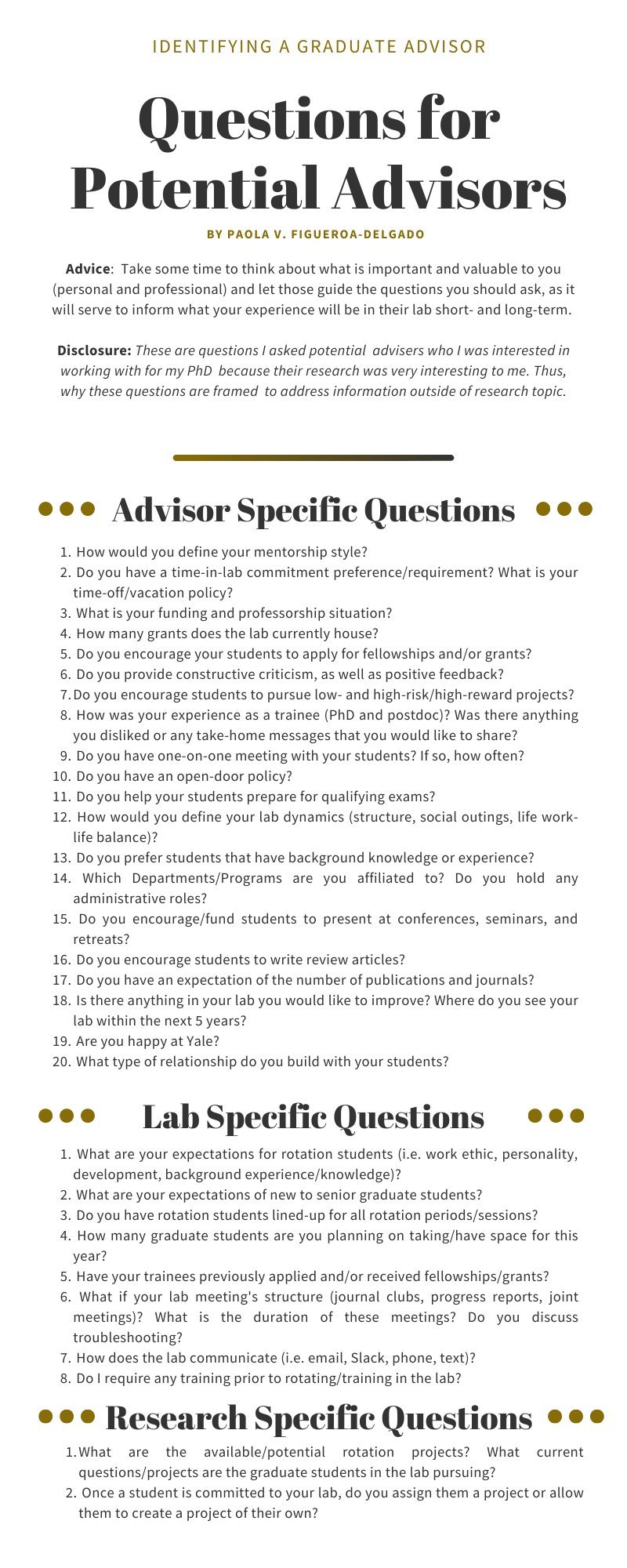

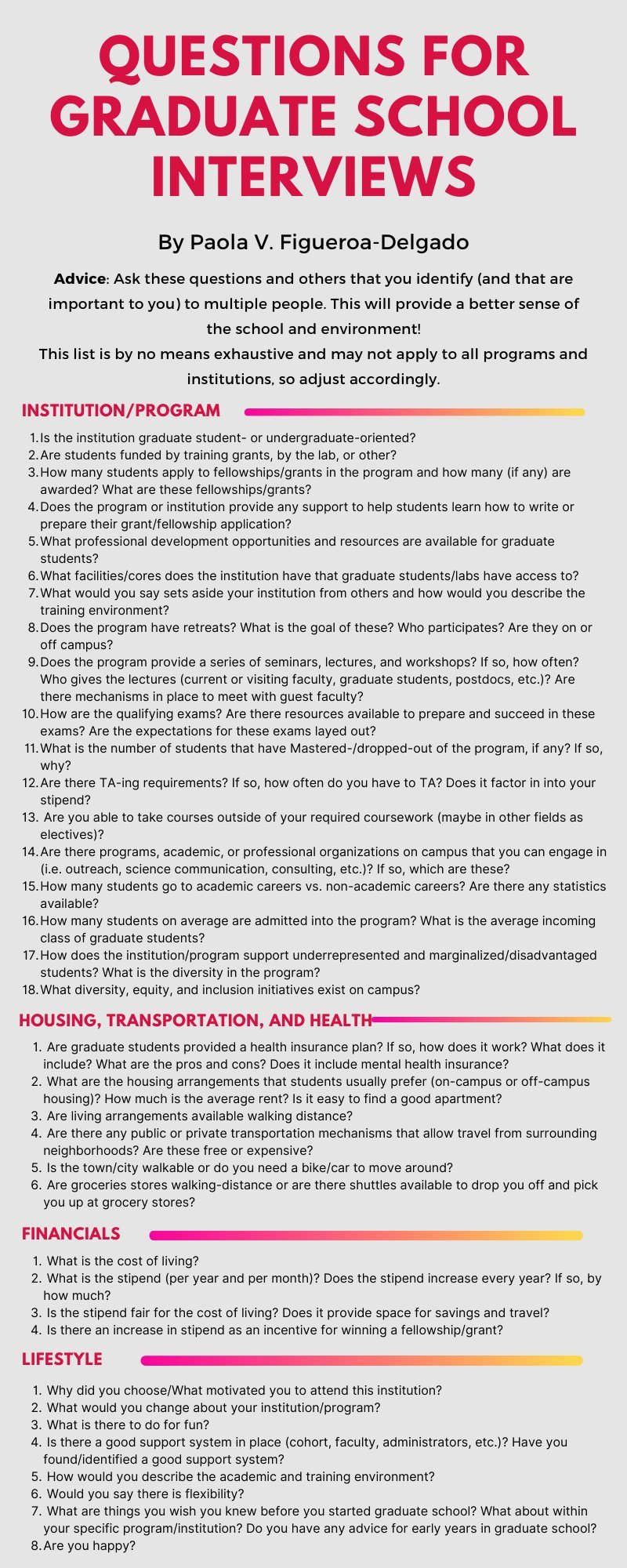

Need good questions? Paola Figueroa-Delgado, a PhD candidate in the Yale Department of Cell Biology, has some excellent resources. See her awesome twitter (ugh…X) thread here, where she provides infographics with lists of excellent questions to ask when looking for the right PhD advisor and during interviews. With permission, here are those infographics:

That’s all for now. Best of luck on your journey through academia.

@dgonzales1990 tweet: “I love academia. Started at the bottom and now here I am 12 years later just slightly above the bottom.”